River Foodway in Concrete Plant Park (unspecified date).

Photo by Liana Smale

Next time you walk through one of New York City’s 1,700 public parks, take a closer look at the names on the signs advertising park events, or at the shirts worn by people picking up trash. Do they say “NYC Parks” or the name of a private group? While NYC Department of Parks & Recreation (NYC Parks) performs many general park maintenance tasks, oftentimes private groups ensure that parks are clean, safe, and fun spaces.

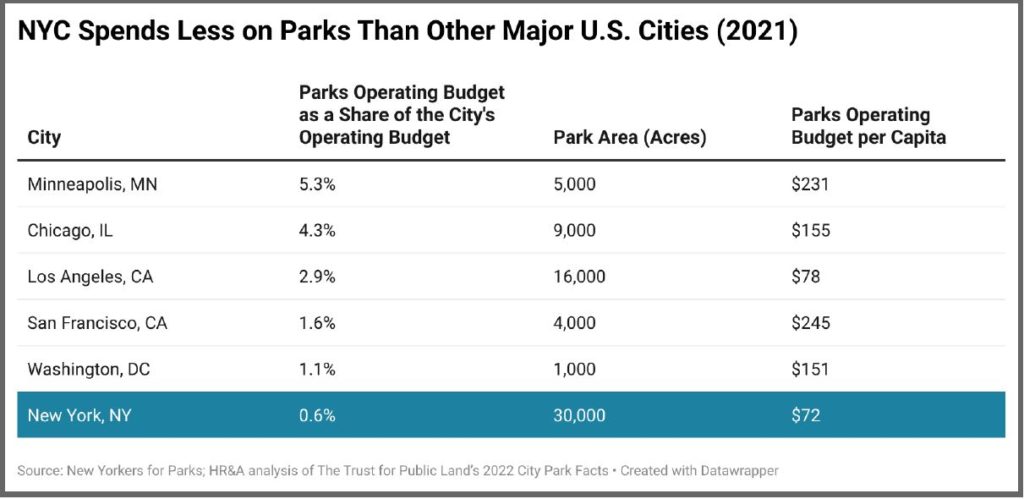

According to New Yorkers for Parks, the City already spends less on its parks than other major U.S. cities, and this June, according to New Yorkers for Parks, based on the preliminary budget, the City plans to cut the Parks’ budget by $46 million. This would cut hundreds of jobs and resources for maintaining parks, especially those outside Manhattan. [Editor’s Note: NYC Parks disputes this. Please read to the end for more information.]

Over the last two years, I have researched what makes the City’s parks incredible resources to residents. When we think of City parks, some may think of the tourist attractions of Central Park or the High Line, but what we may not realize is that their success hinges upon the strength of public-private partnerships between NYC Parks and private stewardship groups that clean and manage them.

Several stewardship groups are well-funded enough through donations to have an official conservancy relationship with NYC Parks. The Central Park Conservancy has a $200 million endowment according to its website. Groups with this relationship have the capacity to take over the maintenance of their parks and are primarily located in Manhattan.

Parks without a conservancy relationship are maintained by smaller stewardship groups or have no stewardship group at all. These lesser-known and under-resourced parks will bear the brunt of this $46 million budget cut. In an increasingly expensive city, public parks are critical infrastructure that provide space to connect with friends, family, and neighbors for free. For families without yards, they function as community backyards. Many contain water features as respite from hot summer days, and green space itself cools dense cities like New York City, according to an Aug 9, 2019 article by The New York Times entitled, “Summer in the City is Hot, but Some Neighborhoods Suffer More.”

We need to remember that funding public parks is a social justice issue. People of color have less access to parks in U.S. cities, according to the Trust for Public Land, and are more likely to live in the hottest areas, according to the website, AGU Advancing Earth & Space Science. In The Bronx, local activists have formed park stewardship groups in response to the City’s historic disinvestment in public parks. For example, in a South Bronx park, the Bronx River Parkway flourishes at the site of an old concrete plant, according to the Bronx River Alliance.

Photo by Liana Smale

The Foodway is maintained by the nonprofit, The Bronx River Alliance, and the community group, Concrete Friends, along with Intervine, a workforce development program that places its trainees in environmental, field-based jobs. It is the only public park in New York City where foraging is allowed, providing visitors with herbs, fruits, and vegetables.

In 2022, the Alliance’s events at the Foodway also included free COVID-19 tests and food giveaways. But many other stewardship groups are stuck at the stage where the Bronx River Alliance began. With the majority of donations going to Manhattan park groups, smaller groups are left to compete for grants. If parks had more support from NYC Parks, stewardship groups could focus more on community-building activities without the burden of consistent maintenance. The government has the responsibility to fund public spaces; low-income communities should not be forced to rely on donations and grants for basic park upkeep.

NYC’s public parks and the groups that steward them are a critical infrastructure that the City sees as amenities when making its budget. New York City Mayor Eric Adams campaigned on the platform to raise NYC Parks’ budget to 1 percent of the City’s budget, saying, “Dedicating just 1% of the city budget to parks would bring us closer to the more generous and forward-thinking funding levels of decades past.” I couldn’t agree more, which is why I’ve proudly committed to a “percent for parks” plan!

But in 2020, the City instead cut $84 million from Parks, according to a March 13, 2023 article by The New York Times article entitled, “One Percent of the Budget for Parks? A Bargain Says a Nonprofit.” Over the next year, Manhattan only saw a 1 percent decrease in cleanliness ratings, according to an NYC Parks Inspection Program, while The Bronx saw an 8 percent decrease. Cutting NYC Parks’ budget by another $46 million in June will further widen the gap between who has access to safe and clean parks.

The debate about public park funding is timely, but it is also a deep, systemic issue where race and income have historically been strong indicators of urban park accessibility. I recognize that New York City needs to balance multiple budget priorities, but access to public, open space is inherently tied to physical and mental health, which benefit all.

Source: New Yorkers for Parks (Table redesigned by Liana Smale using Datawrapper)

If you are a council member, I encourage you to pressure the City’s administration to, at least, maintain the Parks budget, which still only accounts for 0.6 percent of the City’s overall budget. If you are a City resident, I urge you to tell your local council member that you care about public park funding and demand that the City does too. As Mayor Adams, himself, said “Parks are not a luxury, it’s a necessity.”

Liana Smale is from New Haven, Connecticut, and is a Master of Environmental Science candidate at the Yale School of the Environment at Yale University. For the past two years, she’s been researching the New York City parks system to understand its network of private stewardship groups and the environmental justice challenges and successes they have experienced.

She is in the process of preparing a submission to an academic journal about park stewardship in The Bronx and told Norwood News she wrote this op-ed after conversations with the Bronx River Alliance and several other Bronx groups. When asked, she said she is unaffiliated with any particular group.

Editor’s Note: As above, NYC Parks disputes that the Parks’ FY24 budget is being cut by $46 million. Norwood News asked the Parks’ department what figure, if any, its budget is being cut by. We did not receive an immediate response. New Yorkers for Parks who provided the figure to Smale were contacted for clarification.

According to New Yorkers for Parks, “The figure that’s listed in the FY24 Commitment Plan (page 52) in the preliminary budget says $578, compared the FY23 adopted budget of $624 million. Also, the city council’s preliminary response (page 4) listed it as [a] $46.1 million cut from [the] FY23 current budget. The executive budget is now at $610 million but the PEG cuts for FY24 are $35.2 million. Here [are] more budget numbers: executive budget amount: $610.4 million, FY23 adopted budget: $624 Million, total PEG cuts: $53.3 Million, FY23 PEG: $18.1 million, FY24 PEG: $35.2 million, Parks department vacancies: 200 eliminated.”

PEG stands for the Program to Eliminate the Gap, a program already in place since the first year of the Adams administration. In an April 23, 2023 press release, the administration wrote, “In response to the dramatic growth in the cost of caring for asylum seekers and the need to add funds to support labor deals, Mayor Adams implemented a Program to Eliminate the Gap (PEG) in the Executive Budget to reduce costs and promote efficiency. The PEG achieved $1.6 billion in savings across FY23 and FY24 without laying off a single employee or cutting any services. This PEG was applied strategically, and the Adams administration did not remove a single cent from the budgets of New York City’s public libraries or the New York City Department of Cultural Affairs, which funds museums and other cultural institutions, out of concern that reductions in budgets at this time would negatively impact their ability to provide core services.

It continued, “Targets were also reduced for numerous other agencies — including the Fire Department of the City of New York, the New York City Department of Sanitation (DSNY), the New York City Department of Parks & Recreation, the New York City Department of Youth & Community Development, the New York City Human Resources Administration, the New York City Department of Homeless Services, and more — that could not sustain full PEG cuts without jeopardizing public safety, health, or other critical services for New Yorkers. The administration continues to work with agencies to identify ways to operate more efficiently while delivering effective services to all New Yorkers.”